The Conference Board of Canada recently released its annual innovation report card for Canada where the country remains near the bottom when compared with 16 peer countries with a grade of D and a ranking of 13th. Unfortunately Canada’s ranking remains largely unchanged from recent annual grades of D/2011, D/2009, and D/2007 suggesting that Canada’s current innovation activity has essentially plateaued.

Notwithstanding the impact of resource windfall to Canada, the importance of innovation to economic growth remains key to the country’s long-term sustained prosperity. To make tangible innovation improvements over the long-term Canada needs clear industrial strategies aligned with agreed national strengths.

What Canada Does Well

The authors note that Canada is above average in: top-cited papers, ease of entrepreneurship, government online services, new firm density, scientific articles, and aerospace exports. The authors also note that Canada is average in public R&D spending but below average in the remainder.

Why Canada Does Not Perform Well

The view of the authors is that it is still not clear why Canadian innovation does not perform well. The authors note that leading opinions attribute the low innovation performance to public policies such as taxation, heavy reliance R&D tax credits rather than direct R&D funding, regulations, or market structural issues. Also lack of sufficient risk capital, scientists, engineers, or qualified business managers are also mentioned. The lack of industry leaders risk taking propensity or lack of willingness to build globally competitive large corporations. The Council of Canadian Academies prepared an excellent paper on Canada’s weak innovation and business strategy performance that explores these entrepreneurial problems deeper.

Is The Innovation Measurement System Right

The grading system has been continuously evolving and this year improved with the addition of 11 new indicators of innovation performance organized within a structure of creation, diffusion, and transformation of ideas based on the Conference board’s definition of innovation – “innovation as process through which economic or social value is extracted from knowledge – through the creating, diffusing, and transforming of ideas – to produce new or improved products, services, or processes”.

Although improved, the grading system is still not clearly aligned with Canada’s economic and industrial strengths particularly with respect to export trade. For example, the emphasis on export market share in aerospace, electronics, office machinery and computers, and pharmaceuticals is somewhat optimized more for clusters that matured in the 1980s and 90s in Ontario and Quebec. These indicators also reflect the notion that innovation=’high-tech’ whereas we understand today that innovation covers product, service, marketing, and business model innovation not necessarily in ‘high-tech’ sectors. The indicators ignore other strengths where significant innovation is occurring in other regions of the country.

As a result the report card is not particularly useful to drive effective action and decision-making. To really improve innovation performance there needs to be a clear ’cause-and-effect’ relation drawn between innovation activity / investments and economic performance aligned with Canada’s economic strengths defined in terms of industrial sectors. Today the picture remains diffuse, opaque, and unsuitable for defining clear action.

Lack of Industrial Strategy

Canada lacks coherent and comprehensive industrial strategies for key sectors that reflects the structure and strengths of the economy. To do this Canada needs to agree on what are and what will be Canada’s economic strengths going forward.

The authors speak of the need for coherence across all the innovation indicators to score well on the report card. The problem with the innovation indicators is that they are measured as an aggregate evaluation of the Canadian economy as a whole and do not go deep enough to understand how the innovation performance aligns with Canada’s economic and industry strengths sufficient for political and industrial leaders to develop coherent and comprehensive industrial strategies.

Canada’s Export Trade Mix Has Changed Dramatically

Furthermore, over the last twenty years the nature & mix of Canada’s exports has changed dramatically. There is a misalignment in the innovation export ratings between the limited set of ‘high/medium tech’ export indicators with the actual economic structure of the economy. Canada’s top 5 exports in 1992 were Autos & parts, computers & electronics, oil & gas, paper, and primary metals. By 2008 had changed to oil & gas, reduced autos & parts, chemicals, primary metals and machinery. Was this because of a coherent and comprehensive industrial strategy or is Canada simply drifting in the global economy? Canada appears to be struggling with a view of economic strategy set in the 1980s and 1990s with the traditional ‘hewers of wood and drawers of water’ economic view as well as how the knowledge economy fits in an integrated picture.

Part of the problem is that Canadian political and business leaders can’t clarify and define where Canada needs to focus its strengths with recent debates on energy strategy, importance of clean tech, and challenges of the automotive industry. Regional and provincial politics confuses this debate as does the shifting economic power within the country.

Agreement needs to be reached on what are Canada’s top economic strengths, key industries, and how the federal and provincial economic development strategies should be aligned to maximize the outcomes from these strengths/industries. No more drifting, Canada needs then to develop comprehensive industrial strategies that build on its strengths and clarify how Canada’s unique R&D infrastructure (universities included) align to support these strategies. The report card should then be aligned with the structure and strengths of the Canadian economy to be more useful to public and industry decision makers.

Innovation Stuck in Universities

How university research is aligned with national industrial strategies is relevant to innovation performance because Canada is an outlier in the volume of research conducted in universities as opposed to innovation performed in industries. Canadian industry either can’t or won’t perform R&D and universities traditionally have been better able of performing R&D given the structure of the Canadian economy (98% small and medium enterprises who perform little R&D and few large corporations that do perform R&D).

A long-standing issue remains that although idea creation is happening in the universities, the ideas remain stuck in the universities and the economic benefit from commercialization of the ideas is not happening. There are many reasons for this issue such as the distinction between pure and applied science, misalignment between university researcher priorities and commercialization, IP ownership, political jurisdictional power struggle between federal research funding and provincial responsibility for post secondary education, and weak academic/industrial relations to name a few. Politicians are beginning to drive change, as in Alberta recently, but university researchers continue to resist in the name of academic freedoms. Fundamentally relying on universities to conduct applied research that can be commercialized and how this activity is aligned with industry strategy must be resolved. Various incubators and technology transfer organizations across Canada are trying to solve this problem at local levels but outcomes remain minimal in economic terms.

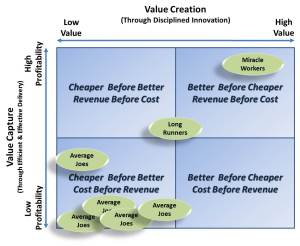

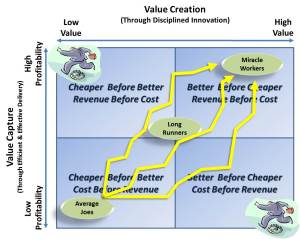

Weak Product Development

With the lack of industrial strategies Canada is not investing wisely in starting and growing enough high quality product firms that can create/design new or improved products with their long-term cash flow generation potential driving sustainable economic potential aligned with Canada’s strengths.

Most economic debate focusses on the decline of manufacturing and fails to clearly communicate the importance of design in an integrated product design/build model to growing companies into world players. Product firms that reach global competitive size such as Bombardier and Blackberry are rare in Canada. The strategic importance of the ability to create new or improved products is under emphasized. While supply chains have gone global and the build function has moved off shore significant innovation occurs in the product design/build development capability. The product design/build development capability is crucial for economic development, anchoring businesses and their headquarters, and enabling the growth of small firms into large multinationals over several decades. Reframing the manufacturing debate was recently well articulated in the context of the US economy in an MIT study of production in the innovation economy (PIE).

The new Canadian start-up visa is a positive step to drive more innovation through new product development but how will candidates be selected and do their ideas align with Canadian strengths. What are the priority industries and how was this determined? Will they become frustrated if Canada’s small venture capital market does not support their ideas?

Importance of Innovation To Restart Economic Growth

The debate on the importance of innovation in driving economic growth is front and center in leading diversified advanced economies like the US, as the MIT study demonstrates, as well as in the UK. The importance of encouraging innovation and R&D investments in strategic industries for sustainable growth is understood to be a long-term national strategic matter. For example, the UK has identified eight priority technology areas with significant funds investments and suggestions for catalysts such as “grand challenges” and ” demonstrators” are proposed. In the UK, there is a clear national alignment between industrial sectors, industrial R&D, university based technology development with overall economic development which provides a model for Canada’s economic innovation strategy.

Canada has some work to do to improve innovation performance. To deliver tangible gains Canada needs to agree on what are and what will be Canada’s economic strengths going forward particularly in the knowledge economy. With a solid definition of Canada’s strengths industrial strategies can be developed in a collaborative manner between the various levels of government and industry leaders. With clear ’cause and effect’ investment and effort decisions can be more effectively aligned through long-term industrial strategies. Only then will Canada see improvements in innovation performance.